Insights into The Birth of Public Adjuster Licensing: Examining Historical Motives from 1921 (Part 1)

In researching the origins of public adjuster licensing, the historical record provides fascinating insights into the mindset of early insurance regulators. A particularly notable document from 1921 captures Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner Thomas B. Donaldson's candid views during a period when states were first implementing licensing requirements.

As noted in a similar article, things have changed greatly in the over 100 years since this meeting that created public insurance adjuster licensing took place. This article aims to provide a snapshot of a document I was not aware of, until 2024.

Hostile Views Toward the Profession

The commissioner's statements reveal some concerning perspectives about the underlying motivations for regulation. Rather than focusing primarily on consumer protection or professional standards, Donaldson made several striking declarations about the profession itself:

"If any man came to me and asked my advice, saying that he contemplated becoming a public adjuster of fire claims, I would say to him, 'You have a very small chance of remaining honest. You have every possible chance of becoming a trimmer, trickster, liar, perjurer and briber. Eventually you are almost certain to be indicted.'"

This sweeping characterization of an entire profession merits attention, particularly given its source was a key architect of licensing requirements.

The commissioner further asserted,

"an inviolable rule that no honest man needs to pay 10 per cent of his claim to a public adjuster and no honest man can afford to pay a public adjuster 10 per cent or any percentage."

Such statements suggest the regulatory framework may have been designed with goals beyond mere professional oversight. Indeed, Donaldson explicitly stated his intent to "drive the public adjuster out of business."

Demographics and Bias in 1921

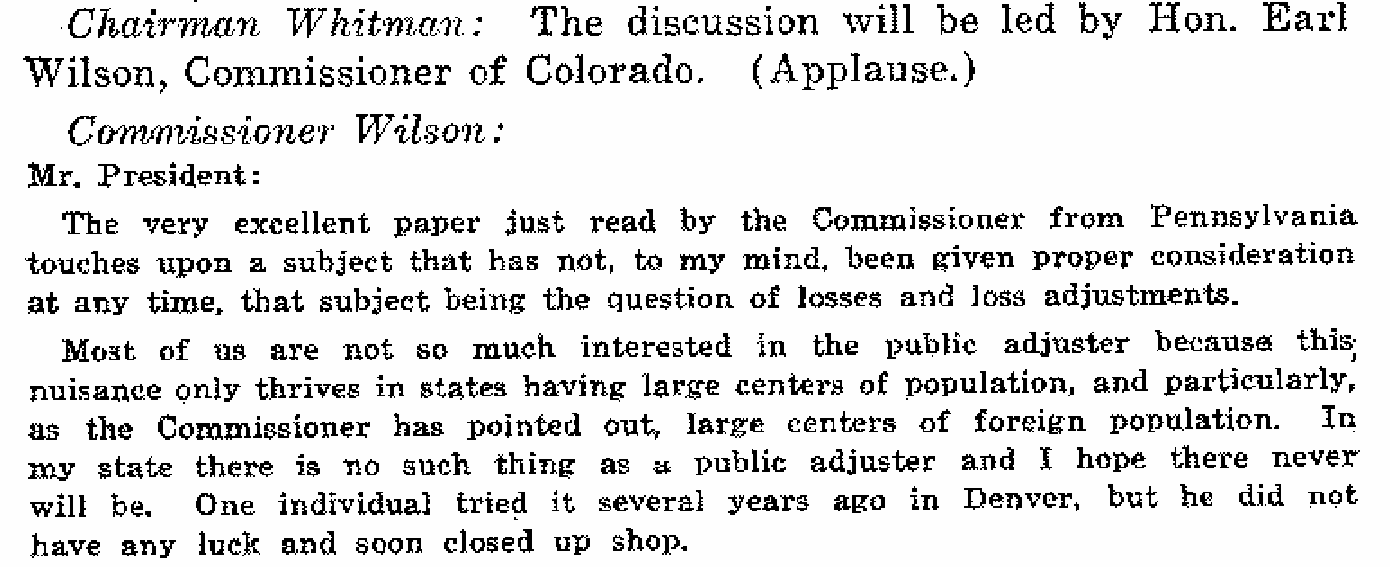

Earl Wilson, the Commissioner of Colorado, made a statement that reflects the attitudes of the era:

"Most of us are not so much interested in the public adjuster because this nuisance only thrives in states having large centers of population, and particularly... large centers of foreign population. In my state there is no such thing as a public adjuster and I hope there never will be."

While this language reflects demographic biases common in 1921 America, it's important to understand it within its historical context, and how it may have affected motives and circumstances behind the initial push for licensing of public insurance adjusters.

Claims Data and Regulatory Response

The historical context is particularly interesting when examining claims data. The document notes that in 1920, claims involving certain public adjusters resulted in higher payments from insurance companies. While this could indicate previous underpayment of claims, regulators interpreted it differently:

- 1918: Average per fire loss - $837.00 (equivalent to approximately $14,400 in 2024)

- 1919: Average per fire loss - $919.00 (equivalent to approximately $14,800 in 2024)

- 1920: Average per fire loss - $1,630.00 (equivalent to approximately $22,300 in 2024)

These figures, adjusted for inflation, show a significant increase of over 50% in average claim payments during this period, which sparked regulatory concern.

The commissioner viewed this increase not as potential evidence of previous underpayments, but as proof of problematic practices requiring strict regulation.

Industry Self-Reflection

Interestingly, the commissioners acknowledged systemic problems within the insurance companies themselves. They noted that companies were failing to properly manage their own adjusters, creating conditions:

"similar to those in many of our banking institutions where men handling large sums of money are greatly underpaid."

They conceded that,

"wherever you find a crooked adjuster for the assured, you are sure to find a crooked adjuster for the company."

Licensing as Control

The commissioners' discussion revealed that licensing was seen primarily as a method of control rather than consumer protection. As one commissioner stated,

"License under the strictest possible condition is the only available influence that can be made use of... as [it] is interfering with a very lucrative business which will not be readily surrendered."

Questions for Modern Consideration

These historical insights raise important questions for current policy discussions:

- How do these original motivations compare to modern regulatory goals?

- What role should historical context play in evaluating current licensing requirements?

- How can we ensure regulatory frameworks serve both consumer protection and fair claims advocacy?

While effective regulation serves an important purpose, understanding the historical context helps inform ongoing discussions about appropriate oversight of the public adjusting profession.

Looking at this history suggests value in periodically reviewing whether current licensing requirements align with contemporary professional standards and consumer needs, rather than perpetuating historical biases.

What are your thoughts on how this historical context should inform current regulatory frameworks? We welcome your perspectives in the comments below.

Citations and References

- Proceedings of the National Convention of Insurance Commissioners, Louisville, Kentucky, September 27-30, 1921. Insurance Commissioners' address on "Licensing Public Claim Adjusters" by Thomas B. Donaldson, Insurance Commissioner of Pennsylvania, pp. 196-207.

- Inflation calculations based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator (www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm)

Note: Commissioner Donaldson's original paper is referenced as being included in the appendix of these proceedings. I will write a separate article for that paper.